The first collision occurred after the driver of the 07:18 from Basingstoke to Waterloo saw a signal in front of him abruptly change aspect from green to red without going through any intermediate yellow aspect. As required the driver stopped his train at the next signal post telephone to report that his train had passed a red signal to the signalman at Clapham Junction 'A' signal box. He was advised there was no fault and that he was free to proceed. The driver told the signalman that he intended to make a formal report when he reached Waterloo. As the driver hung up the phone his train was hit from behind at a speed of about 40 mph (65 km/h) by the late-running 06:14 from Poole running under false 'clear' signals. A second collision a short time afterwards involved an empty train leaving Clapham Junction hitting the wreckage. A 4th train approaching also under false signals at the time managed to stop about 70 yards (60 m) clear from the rear of the Poole train.

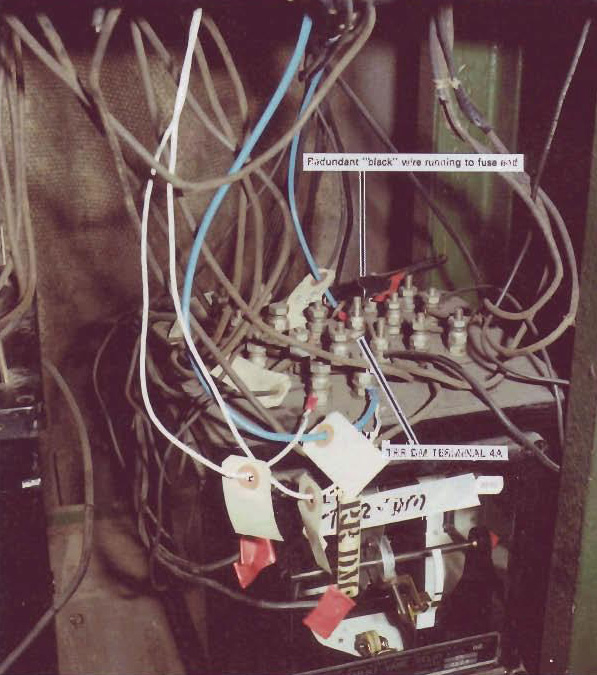

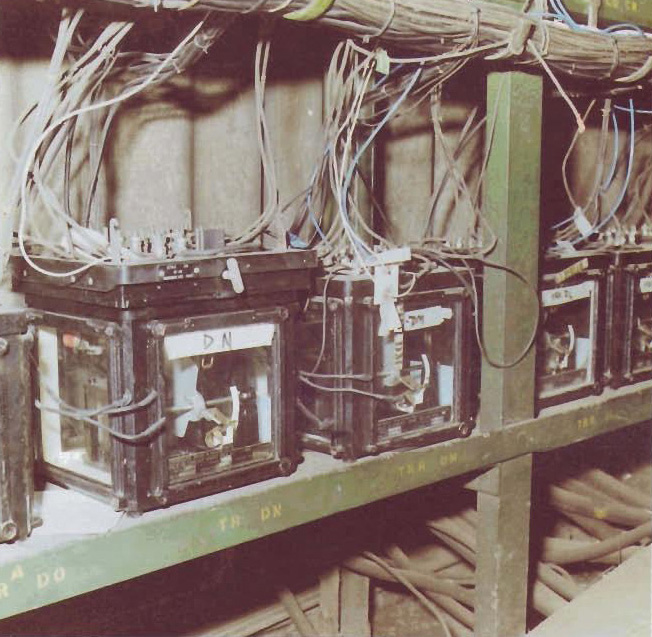

The direct cause of the disaster was sloppy work practices in which a stray wire (bare) created a false feed to a signal relay terminal, which caused a signal to show green when it should have showed red. A contributing technical factor was the lack of double switching in the signal relay circuits, which would have prevented a single false feed causing an accident. The larger cause of the accident was the failure by BR senior management to recognise that the re-signalling of the Clapham Junction area - and indeed the re-signalling of all the lines out of Waterloo, of which the Clapham Junction work was a part - should have been treated as a major, safety-critical project under the control throughout of a single, senior, named project manager. It was left to middle level technical staff, stressed, poorly supervised by their seniors and poorly supported by their juniors, with inadequate staff levels and grossly overworked (some staff had worked seven days a week for two months) to carry out the complete re-signalling of the largest and on some measures the busiest junction on the whole British Rail system.

The Hidden Inquiry into the Clapham rail crash found that a supervisor had noticed some loose wiring during an inspection but had not told anyone about it because he did not want to "rock the boat". The supervisors reluctance to raise the issue was characteristic of a form of self-censorship which organisations such as Public Concern at Work (PCaW), founded in 1993, have sought to overcome. In latter years, the balance between confidentiality and safety (or in other milieu, societal accountability) has been addressed in part by so-called "whistle blowing" legislation such as the UK Public Interest Disclosure Act (1998), and similar provisions in other countries.

The inquiry also recommended the introduction of the Automatic Train Protection (ATP) system; however the inquiry's recommendation was not acted on. Subsequent crashes such as at Southall in 1997 and Ladbroke Grove in 1999 led to further recommendations for the introduction of ATP, and although it has been installed on some lines, it has not to date been specified for the entire network. In the statement on the Ladbroke Grove crash, the Department for Transport sought to make the point that "no workable system was available in Britain" at the time.

Any recommendation for enhanced safety systems must assume absolutely that those systems are correctly installed and correctly maintained. Unlike a manually-operated signalling system, where safety-critical decisions are made by the signalman every time a signal is changed or points switched, an automatic system has these decisions wired in at the design and construction stages. If the design and construction are flawless, the decisions will always be correct. If faults occur, whether as a result of equipment failure or (as here) from human error in the relay room, the decisions will be arbitrary. It is not apparent, therefore, that ATP on the lines out of Waterloo would have prevented this accident, since the ATP could have also been bypassed by the false feed wrong side failure.

A memorial marking the location of the crash site is to be found atop the embankment above the railway on Windmill Road by Spencer Park, Battersea.